- Home

- Tracy Sorensen

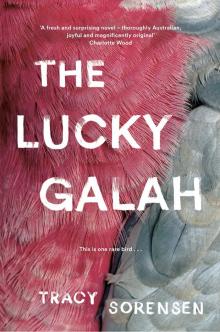

The Lucky Galah

The Lucky Galah Read online

About The Lucky Galah

A magnificent novel about fate, Australia and what it means to be human . . . it just happens to be narrated by a galah called Lucky.

It’s 1969 and a remote coastal town in Western Australia is poised to play a pivotal part in the moon landing. Perched on the red dunes of its outskirts looms the great Dish: a relay for messages between Apollo 11 and Houston, Texas.

Radar technician Evan Johnson and his colleagues stare, transfixed, at the moving images on the console – although his glossy young wife, Linda, seems distracted. Meanwhile the people of Port Badminton have gathered to watch Armstrong’s small step on a single television sitting centre stage in the old theatre. The Kelly family, a crop of redheads, sit in rare silence. Roo shooters at the back of the hall squint through their rifles to see the tiny screen.

I’m in my cage on the Kelly’s back verandah. I sit here, unheard, underestimated, biscuit crumbs on my beak. But fate is a curious thing. For just as Evan Johnson’s story is about to end (and perhaps with a giant leap), my story prepares to take flight . . .

“Subtle, disarming and insightful” Rosalie Ham

Contents

Cover

About The Lucky Galah

Title page

Contents

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

A Note on the Dish

Acknowledgements

About Tracy Sorensen

Copyright Page

To the memory of my father

Brian Sorensen

‘This is the fishiest place I’ve ever seen,’ wrote English buccaneer William Dampier during an eight-day stay at Shark Bay, halfway up the Western Australian coast, in 1699. The blue waters of the bay were alive with sea creatures. The following – about a man in horn-rimmed glasses and long socks who falls off a cliff – is a fishy tale. And yet all of it is true, as true as anything can be.

ONE

The Port Badminton Book Exchange

Her shoulder is bony, her sinews defined, making a good perch. Her straight black hair – it’s out of a bottle – hangs like a gentle curtain against my feathers. I can turn my beak into this hair, nuzzle into the scalp, or gently nip an earlobe.

She walks more slowly than I’d like. I want us to hurry up, to get there, but I’m restrained by the pace of her wandering shuffle; by the way she’ll stop entirely, looking down at a twenty-cent piece on the footpath. There it is, sitting like an island in a drying splash of chocolate milkshake. Will her old knees survive if she bends down to get it? Yes. I lean back like a surfer or waterskier as she lowers herself to the ground.

We’re on our way to the Port Badminton Book Exchange that adjoins the True Blue takeaway shop. These twin enterprises, housed in a brick rectangle, occupy a large area of gravelly, grassless dirt between the Caltex service station and the Olympic swimming pool.

I ride like an Afghan cameleer upon his ship of the desert. My face, belly and armpits are pink: a perfect pencil-box mid pink. My wings, back and tail feathers are grey; my crest is white. Charles Darwin, on his trip to Australia in 1836, commented on the ‘excessively beautiful’ parrots he saw; I’m sure he was referring to none other than the pink and grey galah.

The town of Port Badminton sits like a sandy freckle on the top lip of the open mouth of Shark Bay, just below the nostril of the Sandhurst River. The town is regularly whipped by tropical cyclones and inundated by foaming brown floodwaters. A decaying mile-long jetty reaches out into the Indian Ocean over shifting tidal flats. On dry land, yellow beaches give way to acacia shrub and low buildings surrounded by patchy grass and easy-care gardens of geranium, bougainvillea and succulent pigface. A wooden seawall curves at the base of the main street. The water here is flat, becalmed by a spit of mangrove land lying still and brown in the distance. There are date palms, and benches for sitting and watching sea and sky. The main street, perpendicular to the seawall, is a wide, hot expanse of bitumen. There are few cars, few people, moving about in the silent air.

We pause near the doorway of the Book Exchange. From here, we’re in line of sight of the round white dish antenna that sits on a red dune just out of town. It’s like the giant Jesus overlooking Rio, watching and keeping safe. People think it’s dead, but they’re wrong about that. It’s still very much alive, sending and receiving signals. As a galah, I’m genetically predisposed to receive its signals. They’re often – not always – interesting. Particular frequencies can give me a headache.

Lizzie is finishing her cigarette. Nearby, sitting side by side in the dirt, are a black dog and a yellow lemon. Is the lemon with the black dog, or is their proximity a coincidence? The dog lowers its head to lick the lemon. The lemon rolls away. The dog follows it and licks again.

Lizzie blows her cigarette smoke out of one side of her mouth, considerately directing it away from my face. She is watching the dog and the lemon, thinking her own thoughts. Her cigarette is now the tiniest stub of damp twisted paper. Lizzie drops it to the ground and grinds it into the earth with her blue rubber thong, the heel of which has worn down to the thickness of two pieces of paper.

We step inside, watched by the shop assistant with her indulgent little smile. We pause, letting our eyes adjust from outside glare to the relative dimness of the old fluorescent light. The light gives off a faint buzz. It is partly darkened by the silhouettes of dead flies and other insects. There are handwritten signs stuck at intervals around the room: Crime, Sci-Fi, Romance, Adventure and Misc. High on the wall at the back, on little hooks, are pastel crocheted baby dresses wrapped in plastic. Customers can pay cash for the books – the starting price is fifty cents – but they are encouraged to make use of the credit system, in which the value of returned books counts towards a new selection.

Lizzie will take a book from the shelf and show it to me, flipping through the pages. I make my selections according to my mood or line of thought. Some books have soft, pliable covers, easy to shred. Others have hard covers, requiring strenuous effort of beak, claw, muscle. Such books can keep me going for days, or a week, but they’re often more expensive. Sometimes Lizzie is given a job lot of hard-to-shift copies of Reader’s Digest. I’m not so keen – they’re too easy, a mindless snack – but they’re free, so we lug them home in a plastic shopping bag.

A shabby cardboard box at the far end of the counter catches my eye. A new delivery! In my excitement I screech and fan out my wings.

‘He’s spotted the box!’ says the assistant.

‘She,’ mumbles Lizzie.

‘Oh, that’s right – she,’ says the assistant.

She’ll never learn. I’m a female galah. See my translucent red irises, like a glass of red cordial held up to the light? Male galahs have black eyes, opaque, like shiny beads.

We go over to have a look at the box. Good-looking books, some hardback. The urge to start shredding makes the strong muscles in my cheeks twitch.

‘You like this one, Lucky?’ asks Lizzie.

Lizzie holds a small blue hardcover book in front of me. It is The Lore of the Lyrebird by Ambrose Pratt. She leafs slowly through the first few pages. Mr Pratt was the President of the Royal Zoological Society of Victoria and his book was published in 1933. Lizzie skips ahead to the shiny pag

es. Plate 3 is a photograph of a lyrebird in profile, in silhouette, its lacy tail feathers held in an arc over its body. Its beak is wide open in song. Lizzie gazes at this picture. Until now, she has been showing me the book for my delectation, but I can tell that she is starting to take an interest in it for herself. It is to do with the stillness, the extra dimension of quietness that now encases Lizzie and the lyrebird. I feel a stab of jealousy like an electric current. I pointedly turn my whole body around so that I am looking away from the book. This means that I am now facing the shop assistant. She is a woman with a large bosom and a short grey fringe across her forehead. When she sees me looking at her, she starts to sing.

‘Dance, cocky, dance!’ she says.

I dance, coquettishly.

‘Don’t you like this one, Lucky?’ mumbles Lizzie. I can tell she is still gazing at the lyrebird. I continue to dance for the shop assistant.

‘That one’s ten dollars,’ says the shop assistant, raising her voice to speak to Lizzie, as if she were deaf. ‘That’s an old collectable one.’

It is clear the shop assistant believes this figure will put Ambrose Pratt’s monograph out of Lizzie’s range.

‘Righto,’ whispers Lizzie.

I stop dancing and the shop assistant raises her eyebrows. ‘You’re going to get that one, are you? It’s ten dollars.’

‘Yes,’ says Lizzie more clearly, although she doesn’t look up. ‘I’ll have it, thank you.’

‘Are you going to give it to the galah?’

‘No.’

Rage fills my heart. It makes me rigid through the crop, gullet, shoulders, neck.

Not letting go of the lyrebird – she tucks the book under her left arm – Lizzie picks up another book, a small paperback.

‘Do you like this one?’ she asks, holding it up in front of my face. It is The Lucky Country by Donald Horne. I sit stonily, unable to say yes or no.

‘That one’s fifty cents,’ says the shop assistant.

When we step out of the Book Exchange, the dog has vanished but the lemon remains. It sits on the gravel, rocking almost imperceptibly.

Our books swing and bump in the worn plastic shopping bag as Lizzie lights a new cigarette.

Dish: Stand by.

Galah: Roger.

Dish: Tropical Cyclone Steve latitude 25 longitude 113, wind gusts up to 140 kilometres per hour, central pressure 980 hectopascals. Headed this way. Over.

Galah: Roger that.

Lizzie hears my double chirrup sign-off and thinks I’m talking to her.

‘Home soon,’ she says.

We move off in the direction of the boat harbour, where the prawning boats hold their nets up against the blue sky. Lizzie scans the ground. Sometimes she looks up, searching out birds. She rarely looks about at human-eye level. But I do. I like to see what people are doing, what they might be putting into their cars, what they might be chatting about as they stand with one arm on the open door.

I’m thinking about Luck. Luck rides on the wheel of fortune, round and round. The man on the top – Evan Johnson, for example – can find himself falling to the bottom. And the one on the bottom – me, for example – can suddenly be cast to the top, long after she’d given up hope. She might open her eyes, and look about, and realise she is now out of her cage. She might cautiously spread a pink and grey wing, feeling the unused muscles cramp and stretch in unusual ways.

That’s how it was between Evan Johnson and me. On the day his fortunes fell, mine rose.

We pass into the cool, deep shade under the balcony of the Port Badminton Hotel. This is the hotel where Crowbar – the federal Minister for Regional Development – got his nickname. As a young man he’d struck a man about the head and shoulders with a piece of metal cable and was fined for assault. As the story was told and retold, the metal cable became sturdier and larger, until it emerged as a crowbar. Now known as Crowie, you can sometimes see him on television, standing outside Parliament House in his akubra and crocodile-skin shoes.

We glance in through the door, where it is dark with the smell of beer and the Underworld.

Back out in the glare, our eyes adjust. I can hear a wild galah shouting from a branch of the old eucalypt outside the post office.

‘You ask her,’ shouts the male galah. Lizzie looks up, squints into the darker recesses of the tree. ‘No, you ask!’ replies the female. To Lizzie, this is just squawking.

As Lizzie and I pass under the tree, the female galah – young and naive – calls out to me, more quietly, as if Lizzie might be able to understand.

‘Is it true the old lady’s a hundred and twenty years old?’

‘No,’ I reply. ‘She’s much older.’

The galahs are silent in their surprise. I enjoy teasing them.

‘Hello, pretties,’ mumbles Lizzie in the general direction of the young galahs.

A few blocks further along, we turn into Clam Street, where fibro houses on stilts face an expanse of salty, muddy samphire flats stretching out to mangroves in the distance. If you’re lucky, you might see a slender-billed thornbill here, gently calling tsip tsip.

We pass the Johnsons’ house. There are other people there now, but I’ll always think of it as the Johnsons’. Next door, there’s a pale pink house with an oleander shrub out the front. Nobody has ever been seen coming or going from it, although it would appear to be inhabited. After that, it’s the Kellys. Kevin and Marjorie Kelly’s small weatherboard house, complete with crumbling chimney, is much older than the others and sits low on the ground, slightly sagging into it. A long time ago it was painted in a strong blue, but the paint has scuffed and peeled over time, revealing the wind-worn planks beneath. Collected objects decorate the front garden. Some of these – old pots, a wellington boot – are planted with well-watered geraniums. Next to the front gate and letterbox, there is a white-painted swan made out of an old car tyre. Each year, its long sinuous neck drops lower to the ground. The red geraniums planted into its back are rich and perky.

Dish: Dish to Lucky the Galah. Stand by.

Galah: Standing by.

Dish: Incoming rueful thoughts Marjorie Kelly. Sewing room latitude 24.894362 longitude 113.658156 in a stationary position.

Galah: Not now.

Dish: Now. I must dump.

Galah: Roger.

Marjorie Kelly: I think Kev is writing a letter. I saw him get the writing pad out. He didn’t know I was looking. His own breathing is so loud and he’s that deaf, he doesn’t know who’s right there behind him. Nobody writes letters these days. The girls just pick up the phone and ring me. I used to say, ‘This must be costing a bomb,’ but they’d just laugh at me. ‘Don’t worry, Mum, we can afford it.’ I still like to be quick on the phone. Kev’s sitting at the kitchen table with a biro in his hand. I saw him slide the writing pad under the newspaper as I went into the kitchen to boil the kettle. He pretended he was doing the crossword. When I left he would’ve slid it out again.

I love sitting here by myself in my sewing room with a cup of tea, like I used to do.

I spent all day yesterday cleaning out the junk. I brung it back to what it was in the glory days. I lifted the cover up off the old green Pinnock and there she was, was my old friend. I gave her a good oiling, gave her a run. It’s lovely to hear her go again. She worked hard for twenty years making dresses for local ladies. Then they started going to Geraldton and Perth to buy off the rack. A trip that used to take days, they do at the drop of a hat, now. They all have air-conditioned cars. That put me out of business. I even stopped making my own frocks and started wearing stretchy shorts and drip-dry shirts.

Once upon a time, I would’ve been horrified to wear stretchy shorts outside the house. That’s how much things can change.

I miss my frocks.

This one, for instance. Smells a bit musty. This was my maternity frock. I had fi

ve girls, one after the other, so you can imagine I got a lot of use out of it. It was very comfortable, very hardy. You could still wear it now, if you were petite. But it’s too covered up for today’s woman. It’s all gathered from a yoke, falling right down below the knee. Now they just wear a little t-shirt with their bare bellies sticking out. I saw Kev do a double take in the street. I said to Kev, ‘That’s the style these days, they all do it.’ And then a couple of days later we saw it again, another young girl with her swollen tummy showing. I knew Kev wasn’t coping with it. He went red in the face, angry. ‘Out and proud,’ I said to Kev, to tease him.

He said: ‘You don’t know what that means, Marj.’

‘What?’

‘Out and proud.’

Yes, I do. He likes to think I don’t know about rude things. He thinks I’m pure of heart and mind.

Maybe he’s writing his will.

I’ve been going through all the old bits of material. I’ve got scraps from all of them, every dress I ever made. All the girls’ clothes. Not their panties though. I made cotton panties for them until they begged for shop-bought ones so they could be like their friends. Scraps from all the dresses I did for Linda Johnson. She’d come here for a fitting. I’d measure bust, hips, her small waist. She’d hold her long black hair to one side as I measured the length from nape of neck to small of back. I’d get down on my hands and knees, circling her legs, getting the hem level. Then we’d sit out the back and have a cup of tea. I used to mind her littlies. I did a lot of babysitting while she scooted around town in my lovely dresses. Linda brought the compliments back to me. I lapped them up.

This is a piece from the dress she wore to the Moon Ball. It’ll do nicely.

She turned on me in the end. After her husband fell off the cliff at the Blowholes. I went over with a pressure cooker full of soup, but she shouted at me to Get out, Get out. I came in here and cried for days. I was probably also crying about other things. I got it all into one big cry. It’s the same as if you’ve got the oven on, put everything in that needs baking. Not like now, when people will have an oven on for one little thing.

The Lucky Galah

The Lucky Galah